The Real Adventures of Dick Frizzell

Words: Suzanne McNamara

Photography: Blink Ltd.

Working and living in Uptown, trailblazing artist Dick Frizzell loves his life

and his neighbourhood. He believes it is the perfect place to live and work.

At 81, and with 60-plus years in New Zealand’s art world, Dick Frizzell has become one of our most well-known artists. There have been countless exhibitions and four published books. His designs, illustrations and animation have graced many a street poster, record

album, book and television commercial. He is one of New Zealand’s most celebrated and beloved, receiving a MNZM for services to the arts in 2004.

He’s in demand when we catch up, with a revolving door of interviews about his latest book, Hastings: A Boy’s Own Adventure. Peering through the glass door of his studio, I can see Dick at work, standing facing his canvas, paintbrush in hand. Opening the door, he starts talking immediately about real estate and where he used to live in Ponsonby, how his son Josh purchased the family home, and how when he and Jude, his partner since the early 60s, moved to Hawke’s Bay where he grew up and built a big house, but then missed Auckland.

It’s a yarn with all the hallmarks of ‘right place, right time’ and a bit of ‘who you know’ that ends with how he and Jude purchased and

now live – and work – in a commercial building in Uptown. Upon first inspection of the building, he describes the overbearing smell of the former rubber stamp factory, the manky flat across the hall and walking down a dark corridor. But what sealed the deal, he says, “was the magic door opening and there’s this huge New York loft in there with a beautiful interior courtyard. Even though it was too big, because we wanted a small apartment with a big studio, I said, ‘let’s live large and just do it’.”

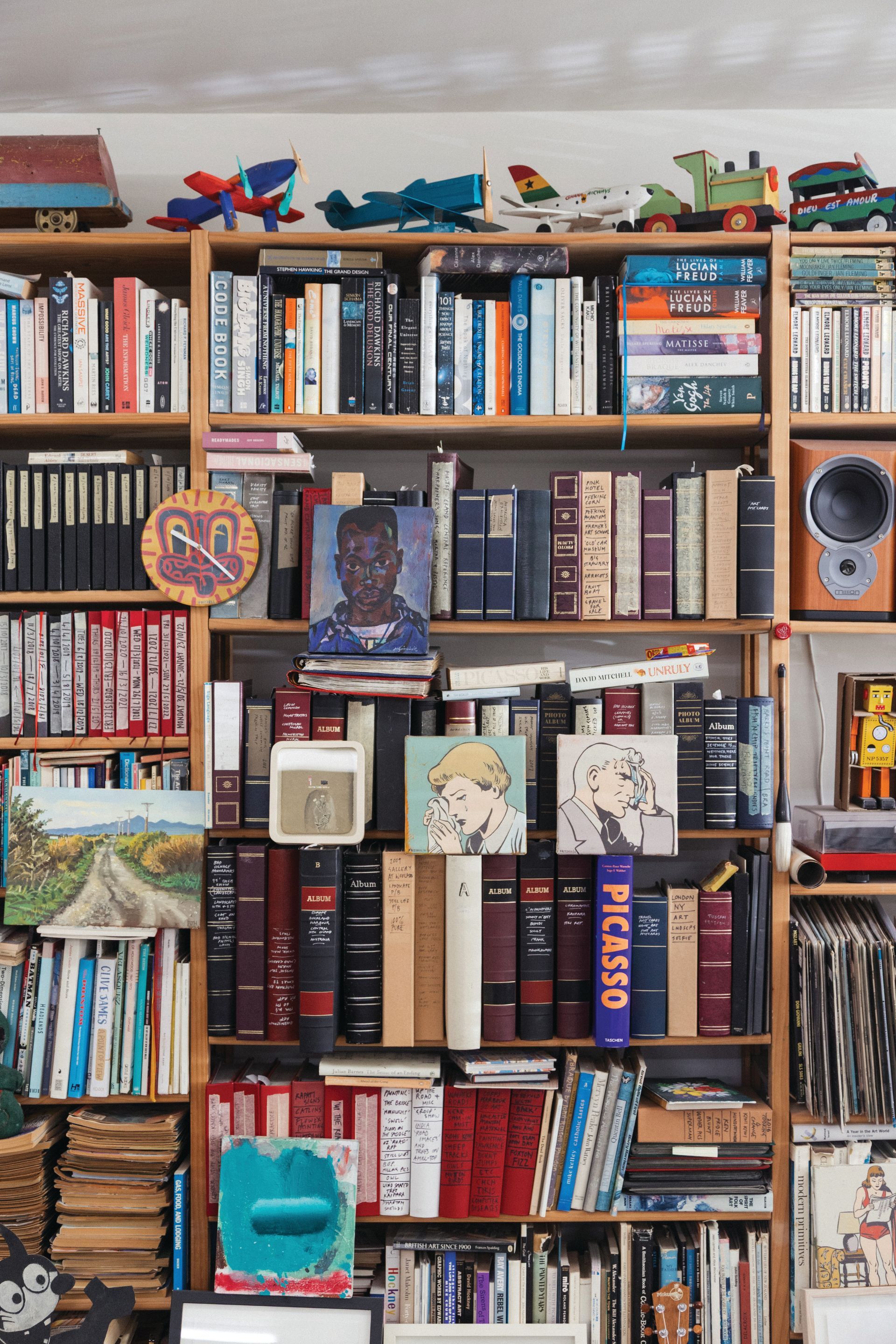

Dick’s studio is at the front of the building. It is a huge space that was renovated into a light-filled studio and is everything you could imagine a studio space to be. Nothing is neat. It is crammed with artefacts “I accumulate rather than collect”, he says with a grin.

On one side of the studio is the canvas and paint. Rags lie discarded on the floor. On another wall, floor-to-ceiling racks store his paintings, while on the other side, there are stacks of books and records and multiple sets of drawers, with every surface and bookshelf brimming. There are doodles and cartoons, many covering the wall above his desk along with family photos. Most striking is a massive landscape on the wall. At nearly 3m wide, it’s a finished piece and part of a body of work for his next show at Gow Langsford in September.

Before we get to Hastings, we talk about his previous three books

and his love of living and working in the area. At first, he wasn’t sure

about the move from Ponsonby, but now says “it’s near perfect”.

He has made friends with all his neighbours; one, the local service

station owner, delivered the NZ Herald every morning while he

was unwell because he couldn’t manage his morning walk to pick

it up himself. He says the delicious smells of baked bread and

pizza wafting up his street from Rosalia’s reminds him of living in

Brooklyn, New York.

Talking comes easy to Dick, he’s naturally chatty – and humorous.

We laugh a lot and it’s humour that permeates his book. It’s full of

rollicking yarns from his Hastings childhood and formative teenage

years.

One of the first stories, loosely based on fact, is about shooting fish

in a barrel with his three friends. “We were kids, we got some fish

and we got a barrel and we got a couple of guns. But it turned out

disastrous because one guy had got hold of his father’s .303.”

It is a funny story because Dick is funny and “the book has hit some

sort of tipping point where everyone’s decided it’s fabulous and

so no one’s allowed to say it isn’t”. The book was already being

reprinted before it hit the stores.

His storytelling is larger than life as he chuckles between punch-

lines. “Well no one got too hurt, but the guy with the rifle blew

himself off the top of the barrel and broke his collarbone because

of the kickback.

“So he’s on the ground screaming in pain and the fish got jammed in

the hole of the barrel. I said, ‘it’s like the frankfurter in an American

hot dog’. And the gun was in the water. It was very comical. There

were the three of us, Huckleberry Finn-like, standing in a half circle

in our bare feet staring at the barrel, thinking ‘what the f#*k?’”

He wrote the story for an RNZ National competition, but it was

pointed out he couldn’t enter because he was a published author.

“They were art books, they weren’t real books,” he says, but still,

rules are rules and as a published author he wasn’t allowed to enter.

That’s when his publisher suggested he should write more stories,

yarns inspired by his teenage years. He wrote one, then another and they started flowing thick and fast. He is already writing the next volume of stories. There’s a sole copy of his new book on his

desk and we turn it over in our hands, complimenting its size, font,

cover and hardback.

Dick grew up in simpler times, when parents didn’t know their kids

were shooting fish in barrels around the back of an orchard shed.

From his anecdotes, it sounds like a good life growing up in Hawke’s

Bay.

Dick’s father was the ammonia engineer at the local freezing works

and got him a job when he was still in high school. “My first job was

down in the pelts department and in those days you worked your

way out to the killing floor. It was the most romantic floor where all

the big swinging dicks hung out.”

Working at the freezing works continued through his university

holidays and he would earn enough to see him through the year at

Ilam School of Fine Arts in Christchurch. With his sense of humour

in play, Dick wrote notes and put them inside the lambs. These

notes caused much hilarity, knowing young butchers would find

them inside the frozen carcasses when they reached London. The

notes said things like “Help me, I’m being kept prisoner”.

At art school, he met the love of his life, Jude. They were barely 20

when the first of their three kids was born.

“No one ever mentioned the word ‘parenting’, that hadn't been

invented,” he says. “You just had kids. They used to run around the

house like guinea pigs, with little thatches of blonde hair. ‘Oh there

goes one, maybe we should feed it’,” he laughs.

He says there was no philosophy to parenting back then. “To be

honest, when we were young hippies, if you had a baby you were

kind of unique and interesting, but no one talked about bringing it

up. You just sort of had it. It was like getting a dog really. Love it,

feed it and house it, you know what I mean?”

He was asked to illustrate a parenting book by Trish Gribben called Pyjamas Don’t Matter, which became very popular in its day. “That was the hippie influence. That was the hippies saying to the straights, ‘if the kid doesn't want to wear pyjamas, let them sleep in their favourite ballet skirt or whatever’. I mean, it’s not gonna ruin them for life or anything. Trish Gribben and I were in total accord with this book: let kids be who they are.”

That attitude epitomised his and Jude’s approach to parenting: not sweating the small stuff, like having to eat so many greens a day.

Dick beams when he talks about his three children. He’s now a great-grandfather and he and Jude visit their daughter Juliet’s grandchildren and their great-grandchildren regularly in Melbourne.

More recently, they had four generations of women and girls in the house for Jude’s 80th birthday. Dick loved it.

“Because we’ve been married for 62 years, everyone asks, ‘how'd you do that?’ I say, ‘well, it just happened’. It’s like saying, ‘how did you stay alive this long?’ I don't know.”

But back in the day with three young hungry mouths to feed, Dick went on a quest to “get into advertising”. Due to his love of cartoons, and talent for drawing them, art directors advised him to visit Sam Harvey, the owner of an animation studio.

“I walked in and I thought, ‘wow, this is amazing’, because Sam was doing all these TV commercials and interesting things and he said ,‘I could do with a hand, but this is a demanding business. I mean do you think you’d be any good?’

“And I said, ‘well, I reckon, because obviously I love cartooning’. So I had to work for him for nothing for a month to prove myself and that was when we did the Chesdale cheese TV ad: ‘we are the blokes from down on the farm’. I animated the short guy in the striped shirt.” That Chesdale cheese ad became one of the most popular TV commercials of the 1970s.

While learning to become an expert animator, he developed a fixation on illustrator and designer Heinz Edelmann, who was the art director of the Beatles’ 1968 film Yellow Submarine and also designed the characters. Inspired, Dick designed the little peanut that used to be on the lid of Eta peanuts. “I designed round eyes that were modern,” he says, but an American from Disney had joined the studio and “he took my drawings and changed them all to oval eyes that represented Disney eyes and I took them back to Edelmann eyes and then we had this huge fight and I stormed out and quit.”

A career in advertising followed. He was headhunted by Bob Harvey to work at his agency, MacHarman Advertising. It was the heyday of advertising, with fat budgets and plenty of scope to develop your own ideas. Dick relished the freedom. “If you thought of a good idea, you could do the whole thing yourself.” They were the new hot shop in town, “we were very young, very mobile and Bob was incredibly daring and reckless,” he recalls.

Dick says while other agencies were “polishing their shoes” Bob would use guerilla tactics he’d learned from his time in New York. “We’d spend the whole weekend on an advertising campaign, very modern, very slick, lots of white space. Bob would make an appointment and show them our stuff and get them all excited and he’d quite often win the account before anyone else got a chance.”

He is candid about his struggle to find his way after art school while he worked in advertising. “I literally couldn't think of anything to paint. I could not think of how you created your own oeuvre. We all knew that as an artist it was all about saying something, it’s your opinion, and I just didn’t know what my opinion was. I couldn’t sort of figure it out.”

After a few years in advertising, something clicked and he found what he had been searching for. “I thought ‘why don’t I go to paintings like I go to advertising, with the same kind of idea that I’m communicating something?’ and then along came this kind of new image thing, this reaction, a global reaction to conceptual art.”

He says art is an ongoing conversation “and if you’re not in the conversation, you’re kidding yourself, and the conversation at that time was ‘we’re getting a bit sick of this conceptual art scene’. A few young people, like me, who loved images, thought ‘how can we smuggle these images into the conversation?’ and then I found a way of doing it – my way – which was treating it like advertising.”

As luck would have it, the times seemed to change in step with Dick. It was a similar story with his landscapes. “It did sort of single me out, because you weren’t meant to be doing them. Serious artists didn’t paint landscapes.”

One art critic said Frizzell was hiding in the hills. “I literally was, I was painting all the hills and hiding in them,” he chuckles. But the landscapes had Dick’s take and were a huge success, with collectors snapping them up.

Already well known by this point, it was his show Tiki in 1992 that caused waves and made him a household name. It contained cartoon versions of tiki, such as the now famous Mickey to Tiki.

Accused of cultural appropriation, Frizzell stood his ground. He says he hadn’t arrived at it with no thought. “I wasn’t just some idiot wading into it ill-informed.” It coincided with Air New Zealand ending its plastic tiki giveaways on flights and the tacky Māori insignia being taken off motel signage in Rotorua.

“I thought that the idea of protecting something, like putting caveats and a fence around it, was fatal. You just choke it to death.”

Modernism and abstraction spurred him to relook at the work he had studied at art school. “In those days you weren’t meant to go back, you were meant to go forward all the time, refining your argument, but I thought, ‘no, you can do whatever you like. That’s the point’.

“The critics said that I had become intellectually lazy and everything else, but I was having fun and making money. It didn’t seem to matter. The sky didn’t fall in, nothing happened.”

And once again he was ahead of the curve. “Going back became a thing. Reiterating and repolishing old ideas proved to be something you could actually do. You can go back to your own rubbish bin and pull things back out and polish them up again.”

Recounting Auckland in his earlier days, he says that “the whole entire creative population of New Zealand could gather in one public bar, almost”. Everyone knew everyone else and he’d be making posters for his mates at Radio Hauraki and Blackie (Kevin

Black, one of the most popular breakfast hosts of the day) would promote his first exhibition live on his show for nothing.

He thinks it must be different for young creatives now “because they’re more spread out throughout the city instead of this one giant rowdy houseful that we had”. Yet the internet has changed the art scene. “You can invent things and crash the scene,” says Dick. His advice to young people is to back themselves, “get excited and stay excited, get obsessed and stay obsessed.” So is Dick Frizzell still obsessed? “Jude would say I am.”

Of course, now he doesn’t need to worry about anything people might say, he is Dick Frizzell. He reflects in a self-deprecating way about blundering into his ideas. “I did it my dumb sort of way, I did it out of desperation more than anything else and maybe everyone blunders into ideas and maybe even the philosophers blundered into their ideas. I don't know.

“All I’ve ever done is tried to stay totally transparent, because you can never get caught out. People can never accuse you of being a hypocrite or cheating or whatever, because it’s just way dumber than that.”

And perhaps this is why we love Dick Frizzell – his innate ability to keep things real.

Hastings: A Boy’s Own Adventure is available at all good booksellers