The Beginning of Newton East

New Zealand historian and author Lynnie Howcroft researches the early days of Uptown.

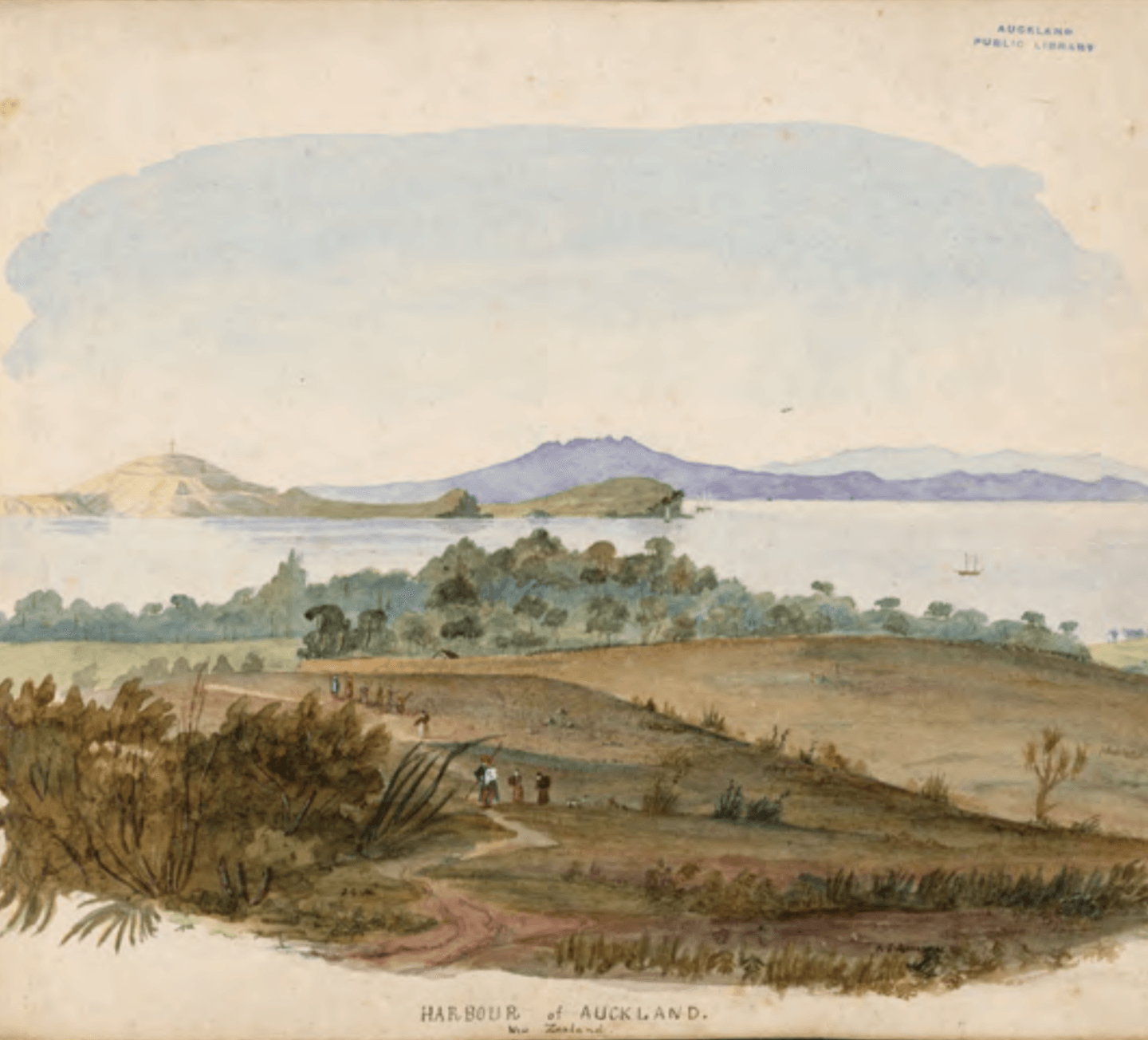

The steep slopes of Newton were a kete kai (food basket) for the tribes of Tāmaki Makaurau as they travelled from coast to coast, traversing the gully’s ridgelines.

For hundreds of years, the peaks now called Karangahape Road and Upper Symonds Street were part of a network of routes that Māori used to practise ahi kā, seasonally cultivating their land, or forging tribal alliances. The karaka and mānuka trees that were known to have grown in this part of the gully, called Te Uru Karaka, could have housed plump kererū (wood pigeon) for the hunter/gatherer to feast on. Fresh water springs that squeezed through the ground near the corner of Upper Queen and Randolph Streets, and that were found to the east of Symonds Street Cemetery, would have formed a creek at the bottom of the gully to quench the thirst of any weary traveller.

(See footnote.)

(Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 3-139-1)

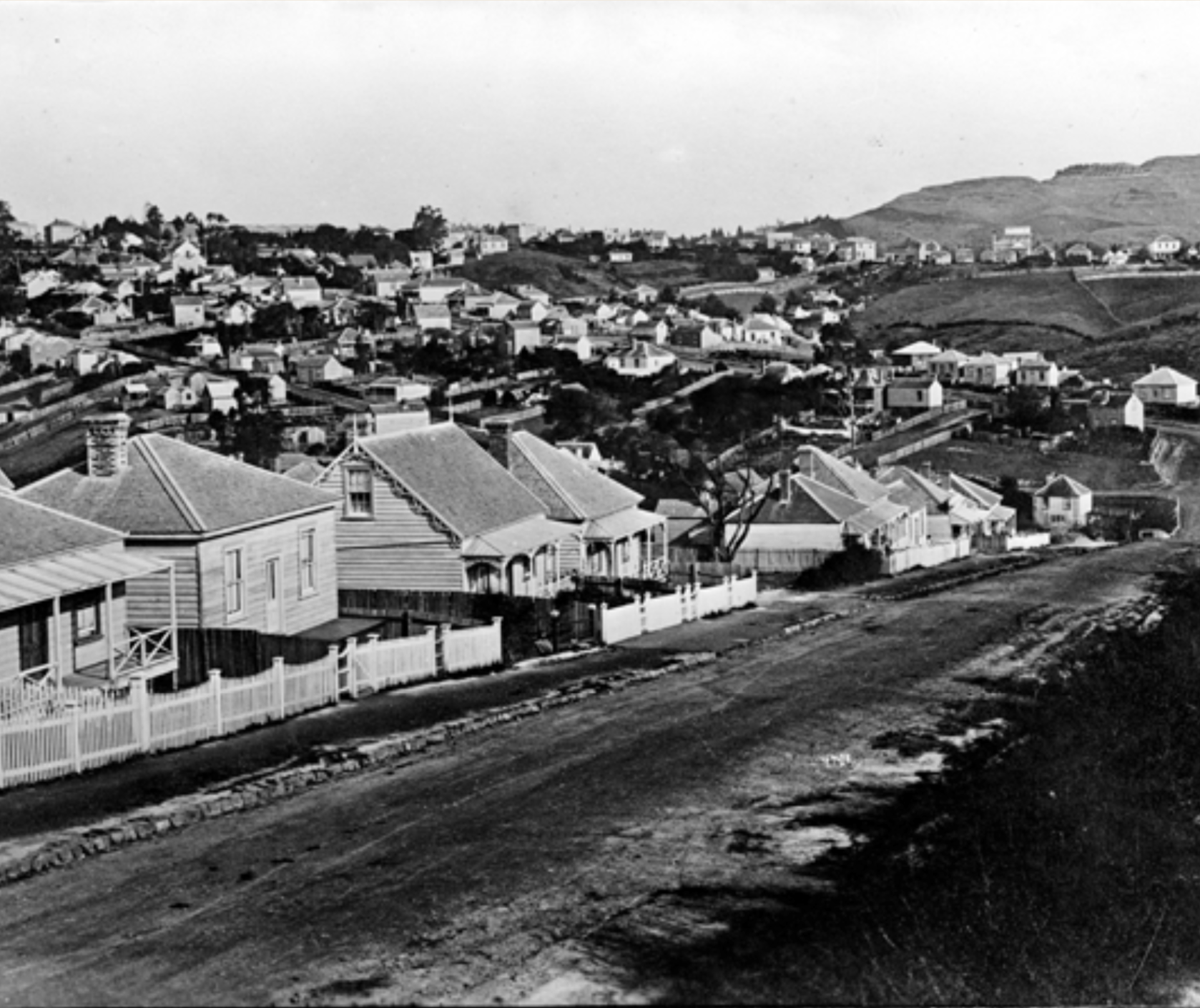

1878: The right angle shape of Newton Road starting from the corner of Mr Probate’s land at the Ponsonby Road intersection. Newton Road meets Upper Symonds Street at the left-hand corner of the photo where there are trees. Maungawhau (Mt Eden) is top right. Eden Terrace, New North Road, sits at the base of Maungawhau. At the bottom of the gully, a block before the Newton Road corner, the culvert was built. This corner has been replaced with the Newton Bridge and the western motorway. (Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 580-6246)

Just as the surrounding ridgelines are a link to the way of life before the arrival of the Europeans, it is the gully’s roads that forge the link to the lives of Auckland’s early colonial settlers.

More than 160 years ago, a “Newtonian” wrote to the newspaper suggesting that a road be built to:

“... lead from the Khyber-Pass Road, at Mrs Fairburn’s, to the North Road at Mr Probert’s made passable ... It would connect the East and West Newton, bring the Cabbage tree people nearly a mile nearer to town, and cut off a long road from Mount Eden for the scoria carts, a very great advantage now that so many improvements are being made in the Western portion of the city.” (Jan 1862, New Zealander, issue 1642)

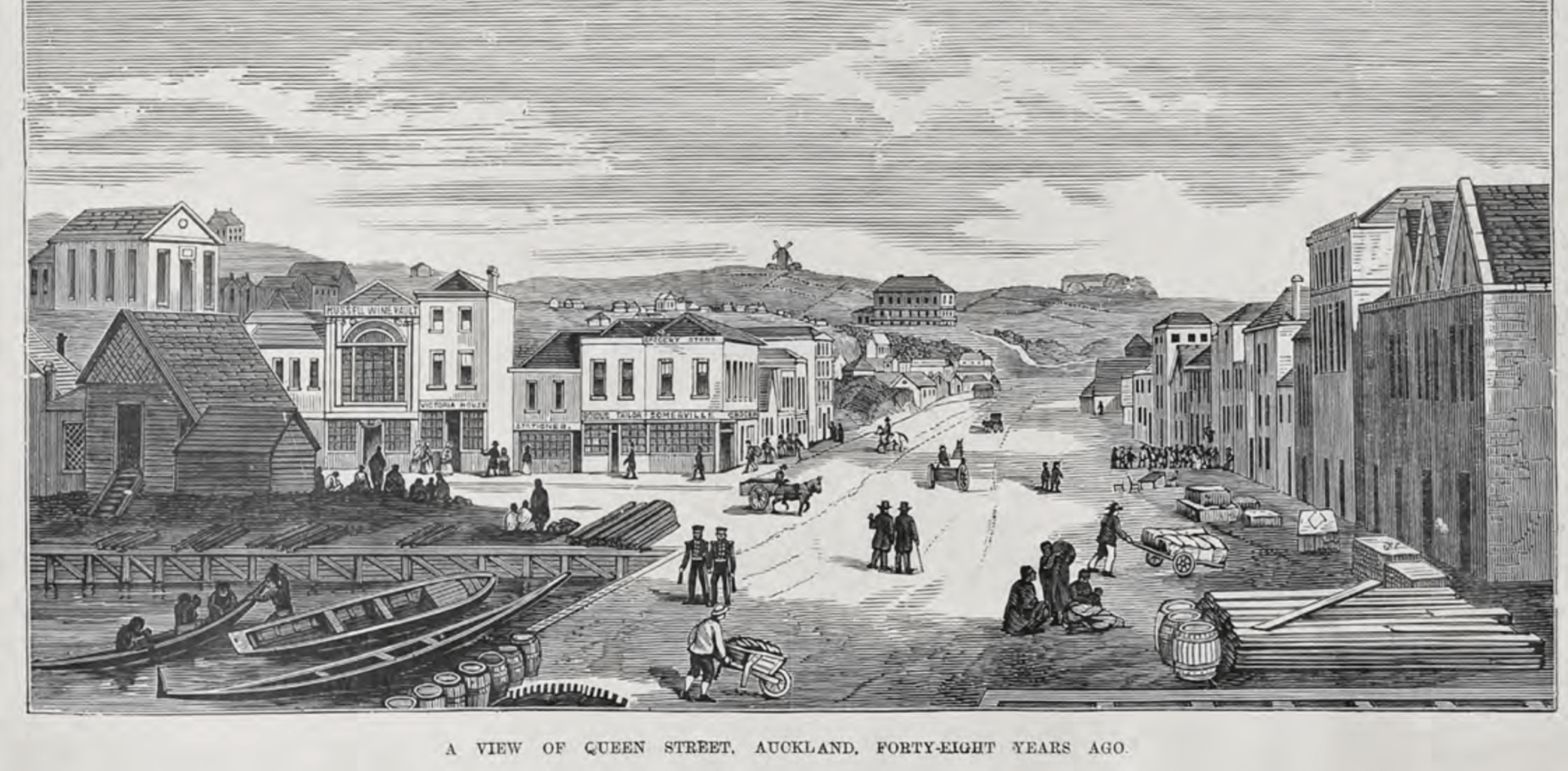

The writer continues, “If the Newton Road be made, the metal carts that were leaving the Maungawhau (Mt Eden) quarry for Ponsonby Road and the lower streets of the City would no longer have to go via the windmill, and along Karangahape Road.”

This Newtonian offers us a glimpse into a time when colonial Auckland was at a crossroad (no pun intended!). This letter in 1862 reveals that Auckland was “on the make”, building an infrastructure to meet the demand to house the many migrants disembarking at the Queen Street wharf. It also appears that the Karangahape Road and the Upper Symonds Street ridgelines had, over the past 20 years, retained their importance as major routes to access Auckland’s town centre and port. But this simple letter also hints at the mindset of an early European settler, whose focus is on expansion, bypassing the old way for the sake of efficiency.

Up until 1862, Māori had continued to use these ridgelines to access Auckland’s town. During the 1850s, wheat that was grown by the Waikato tribes was transported by river, sea and cart to be ground at Partington’s windmill. In an article written about the mill, a quote from an old Waikato rangatira who knew the mill well stated:

“Te Mira Hau held great mana ... Did not Te Mira Hau grind wheat impartially for both (Pākehā and Māori), and if the grain was of equal quality, turn out as good flour for the Māori as it did for the Pākehā?”

The article interpreted his thoughts further: “Such fair dealings in the days of land grabbers and cheating traders deeply impressed the Māori ...”

This old rangatira’s simple but profound statement addresses the reasons that many Māori had lost trust in their Te Tiriti o

Waitangi partners. As successful farmers and traders with the Auckland settlers, Māori had believed that the 1840 treaty would protect them as rangatiratanga (sovereign rulers), and that they would retain their land and their autonomy. But, in 1852, when the British Crown recognised New Zealand as a colony separate from Australia, passed the NZ Constitution Act and, in 1854, opened the first parliament in the capital city of Auckland, Māori were

n

ot represented. In fact, few Māori met the criteria to vote as few individuals owned land in a single title. Imagine their concern as the waves of migrants settling in Auckland wanted to acquire more land. Imagine, too, their dismay as many of their whānau (family) were dying of the diseases that had been brought into the country by these immigrants. By the late 1850s, the European population in New Zealand outnumbered Māori and something had to be done.

At this time, Māori resisted pressure from the Crown to part with more land. This resistance was solidified in 1858 when many of the North Island tribes agreed to unite together under a monarch. After many years of consultation between these tribes, the Ngāti Mahuta chief Pōtatau Te Wherowhero agreed to be King. The tribes that joined the Kingitanga movement gave Te Wherowhero the authority to be the “one voice” to settle land disputes, maintain law and order, and to keep the peace with the Pākehā. The settlers, however, considered this Māori King a direct challenge to British Imperial authority. By 1859, tensions between the races were growing, and it was in this climate that the owners of Newton East gully’s paddocks saw an opportunity and answered the settlers’ demands to own a piece of land. Situated only one mile from the Auckland town centre, blocks of the steeply sloping land were surveyed one by one ready for sale.

In 1862,

only one month after the Newtonian letter suggesting that Newton Road be created, Auckland’s Superintendent called for contractors to submit a tender to, “Cut, Form, Metal the Roadway and to construct a Culvert” so that Newton Road would join Upper Symonds Street and Karangahape Road.

(Feb 1862, Daily Southern Cross #1476)

What prompted the wheels of bureaucracy to respond so quickly is unknown. However, it is important to note that in 1860, the Daily Southern Cross advertised that, “seventy choice allotments that fronted onto Newton Road, sown in clover and fully fenced” were for ready sale. These allotments were first offered as early as March 1859. According to the Newtonian letter, Newton Road had been built, but did not connect one ridgeline to the other.

1852: View from Queen Street Wharf to Partington’s windmill built on the corner of Karangahape Road and Upper Symonds Street. (Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Library AWNS -190000928-4-7) New Paragraph

For the few early settlers who owned large blocks of land between Karangahape Road, Upper Symonds Street and Newton Road, this was a win. The culvert that was built in Newton Road diverted the Cemetery Creek/stream to flow under the road at the base of the gully and, by doing so, created easier access to the outer suburbs.

This in turn would have increased the value of the land in the centre of the gully and the desire for settlers to live and invest there.

The Newton Road residents must have been delighted, as the cost to join this road was paid by Auckland’s Board of Works. The board, therefore, was also responsible for its maintenance. At that time, many of the roads that accessed the new subdivisions were built by land developers and were considered private roads unless legally gifted back to the Crown. Of the gully roads that were considered private, it was the residents’ responsibility to pay for the upkeep of those that accessed their property, or to write to the board for additional funding if the roads were impassable.

While Newton Road was not the first road to connect to the two ridgelines (that was East Street), its development was pivotal to the growth of a new suburb. When subdivided, the gully’s interior blocks of land became integral routes that led in and out of Auckland’s town. Within five years of the sale of the gully’s paddocks, what was first named Newtown had the bones to grow into the vibrant suburb of Newton East.

So, who were these early settlers who first owned land in Newton? As their, and other “Newtonian” stories are told, a community will be revealed that had a grit and determination to survive in New Zealand when times were tough and money was scarce. These humorous and insightful stories will be shared over the coming issues.

1922: View from Newton Central School looking north toward Newton East. Newton Road (far right), Randolph St middle. St Benedicts top left. (Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 4_5265)

1899 map of Auckland city showing the Newton Road connection to Newmarket and Ponsonby Road. Yellow line defines East Newton’s borders 1869-1879. (Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 4-168 1900-1910)