Growth in the Gully

New Zealand historian and author Lynnie Howcroft researches the early days of Uptown.

From the beginning, New Town (Newton) was a suburb that the working classes were drawn to. Perhaps it was the affordable housing that caught their attention, or the size of new allotments that allowed for a modest home, stables, gardens and, if needed, a place of business. As each farm block in the gully was subdivided, there was an abundance of work available for labourers and the semi-skilled workers in the Newton area. Once regular work was found and guaranteed, loans could be secured against a mortgage or regular rents could be paid. For those who could only earn meagre wages in England, to be able to buy land offered security and the right to vote.

Newton’s popularity was explained in an 1862 newspaper article that summarised a subdivision sale in the gully:

“In few parts of the world have working classes had the means or the opportunity (of owning land). In England it would be impossible, yet in this colony (New Zealand) it is a common thing to find mechanics occupying houses, their own freehold ... or find them proprietors of other dwellings which bring them in a weekly rental.” (14 May 1862, New Zealander, Issue 1677, page 2)

In 1860, a letter in the local newspaper revealed that there were around 100 labourers living in the area between Karangahape and Khyber Pass Roads. Stunningly, this was a result of only two subdivisions that released 157 allotments for sale. This indicates that in two years, a large number of these allotments had dwellings built on them. Over the next five years, the remaining subdivisions in the gully released more than 620 allotments into the market. Regular work for labourers who chose to live in Newton was right on their doorsteps.

“Gentleman” politicians and merchants had also invested in the gully, but never intended to live there. Many were speculators who had bought land for profit, or built properties to rent to the new immigrants who were arriving in Auckland weekly.

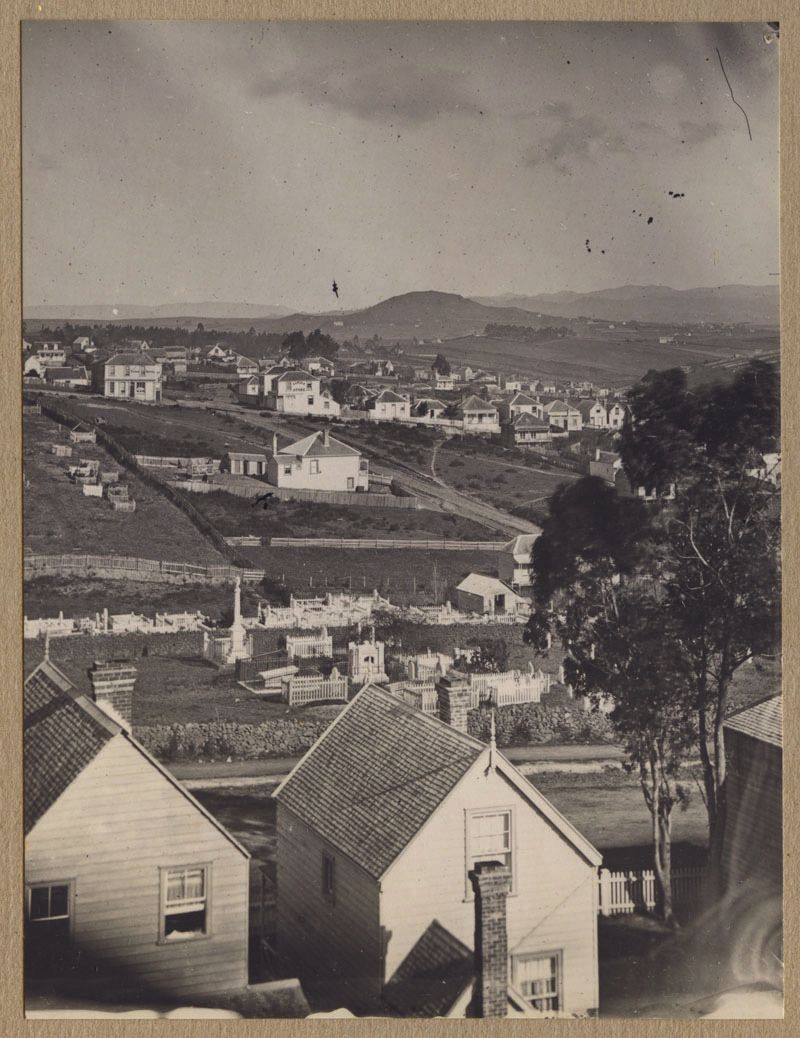

Above: 1870 looking south toward Ōwairaka (Mt Albert) with Karangahape Road in front and Upper Queen Street in the middle of the image. Mr Wilkes Eureka Store on the right. Opposite the York Hotel on the right on the corner of East and Upper Queen Streets. (Auckland Museum Collection) (

For the semi-skilled worker, factories had sprung up around the gully offering employment for those who had worked in similar industries in England. In 1862, George Holdship’s steam timber mill on the corner of West Street and Karangahape Road had replaced the noise of the Laurie Bros’ steam brick factory machine that had been working in the gully since 1854. Employment was also found manufacturing bricks on Gundry’s land and at George Boyd’s factory on Monmouth Street, where multitudes of clay bricks, tiles, drain pipes and Victorian household items were made to grace Auckland homes.

By 1865, on the south side of Karangahape Road, there were a variety of businesses that serviced this new community. There was Brophy’s Post Office, two grocers, a butcher, chemist, two doctors, a boarding house, two bakeries, the Newton Hotel, a few lawyers and a real estate agency. On Newton Road, there were grocers, Mr Stevenson and Mr G Turrell, Howies’ bakery and Fagan’s butcher.

In the centre of the gully, Mr Butler’s paint and paper hanging shop was found in East St and three doors up, on the corner of Upper Queen and East Street, was Mr Wilkes Eureka Store and Athenaeum, where settlers read and conversed about issues of the day.

In 1860, all who had made the gully their home had been conscripted to join the No. 5 Company. Newtonian neighbours of all shapes and sizes reported weekly at the Albert Barracks for military training. Men such as Mr Haslam from the 58th regiment had returned to New Zealand and had also bought in the gully. He was employed by the military to train these volunteers. In 1863, when Lieutenant General Duncan evoked war with the Kingitanga by crossing the aukati (the Mangatāwhiri Stream), Newtonians (such as Holdship, Brophy and Butler) joined the colonial forces to suppress the “rebel Māori”.

Once the Waikato war had ended in July 1864, the Newtonians joined together to fight one more battle. Over the next four years, the neighbours met and formed deputations to the Superintendent (Mayor) requesting help to fix the deplorable roads that accessed their properties. There are records from the time about men sinking up to their knees in mud as they crossed Karangahape Road; in West Street, a glazier was so stuck in the mud that he had to be lassoed out by residents. Carts were often overturned in Upper Symonds Street when they hit deep ruts, throwing passengers out onto the road. On Newton Road opposite the Edinburgh Hotel, a cart and horse fell into a sinkhole, smashing the axle of the cart.

Winter in the gully guaranteed volumes of rain water that would loosen and carry the top level of metal down the slopes toward the creek. The exposed base layer of metal was then trampled into the clay. The result was that every winter, roads in Newton were a quagmire. To remedy this overwhelming problem, an administrative body whose sole purpose was to focus on maintaining roads was formed. The first meeting of the Karangahape Highway Board was held in 1869 for all Newton East residents who owned land in the new district. At this meeting, the residents set their first rates at halfpenny to the pound against the value of their property and board members were voted in to serve for a year. Establishing this board defined the town’s boundaries, and for the next 13 years Newtonians learned about the pitfalls of politics as they tried to tame the gully’s roads into submission.

Above: 1864 Robert Stevenson home and grocery store on the corner of Newton Road and Upper Queen Street (Gloucester Street). (Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 589-134)